There is much to love about Georges Méliès. He was a technical wizard, a delightful performer, and an artist whose gorgeous work can still inspire awe. And charmingly, he was a man who believed in dreams. He captured many of them on the screen, one painted set at a time, and today they serve as reminders of an era more open to wonder.

Méliès’s films have a knack for taking us out of our comfort zones in the most enchanting way possible. They’re so old-timey to our eyes that they could almost come from a different planet. At times, we have to remind ourselves to stop holding them at arm’s length.

But to filmgoers in Méliès’s own time, the filmmaker’s work was not only exceptional but also familiar. In fact, he was drawing upon a long history of theatrical enchantment–specifically, the French theater genre of the féerie.

I nearly pulled my hair out trying to find a picture, any picture, actually depicting a French feerie play, so here’s a general Paris theater scene.

This genre is little-known and little-discussed today, but it’s key to understanding Méliès’s distinct style–and the style of other filmmakers as well. Thought to have largely developed in the early 1800s, it in fact drew upon the elaborate 16th and 17th century ballets commissioned by European courts. Based on fairytales and mythology, some of these ballets were several hours long and were performed at Versailles and other not-too-shabby locations.

Engraving showing a Versailles ballet in 1664.

These luxurious ballets didn’t just feature dancing, but also elaborate costumes, pantomime, tableaux (“living pictures”), singing, and stage magic. The plots, which grew increasingly thinner as the focus shifted to spectacle, featured fairies, witches, imps, gnomes, gods and goddesses galore. It was an honor to write and design these elaborate shows–even big names such as Molière would try their hand at them.

After the French Revolution, theater began to focus on pleasing the bourgeoisie. One of the most popular forms of light entertainment was the whimsical and elaborate féerie, child of the former opulent court ballets. The first official féerie we can point to was Le Pied de mouton (The Sheep’s Foot), written by Alphonse Martainville and first staged on December 6, 1806. It was the model for all the plays that followed throughout the 19th century: hero Guzman goes on a quest to rescue his lover Leonora from a villain, and encounters many obstacles and strange sights along the way. Not too far removed from today’s road films, but more in favor of the imagination and the timeless showdown of good vs evil.

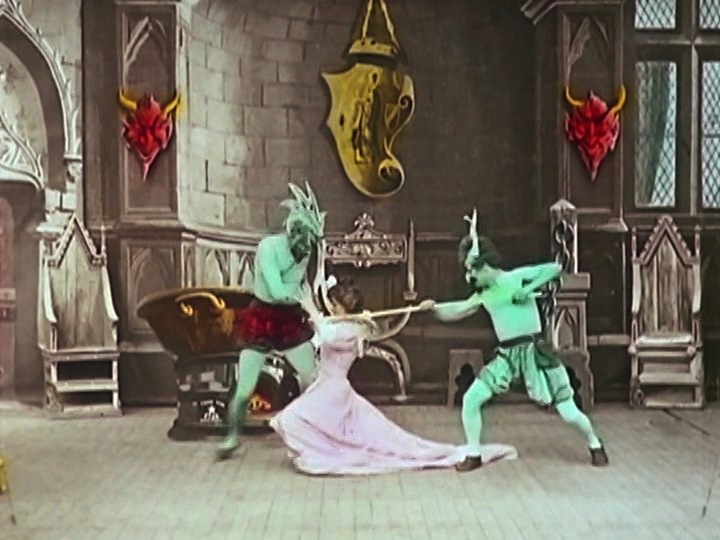

A wonderful still from a 1907 film version of the play, by Albert Capellani

As you can tell, the plot left room for as much spectacle as possible. Designers were free to make as many beautiful settings as their budgets allowed, and writers could come up with any surreal scenarios their hearts desired. Magicians went to work creating eye-popping illusions (characters transforming into different beings was especially popular). Actors had the fun of portraying nymphs, fairies, devils, wizards and other supernatural beings.The overall goal was to capture dreams, to present lovely and oftentimes thrilling escapes for their audiences. Theater critic Théophile Gautier wrote in 1869:

What a charming summer spectacle is a féerie! That which doesn’t demand any attention and unravels without logic, like a dream that we make wide awake…a symphony of forms, of colours and of lights…The characters, brilliantly clothed, wander through a perpetually changing series of tableaux, panic-stricken, stunned, running after each other, searching to reclaim the action which goes who knows where; but what does it matter! The dazzling of the eyes is enough to make for an agreeable evening.

At the end of the 19th century theater owner Méliès was part of the French entertainment scene. Having grown up in Paris near many theaters that put on féerie plays, he was well acquainted with the genre. And he certainly had a fondness for the marvelous. Once he turned filmmaker he began to stage elaborate fantasies, capturing the charm of the féerie while adding his artistic stamp. French audiences would’ve recognized his use of trap doors, moving scenery, tableaux and costumed chorus girls as familiar féerie staples.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea or Under the Seas or, no kidding, Deux Cents Milles sous les mers ou le Cauchemar du pecheur (1907).

Other filmmakers would make féerie-inspired plays too (Segundo de Chomon is a notable example) but few could match the ingenuity of Méliès. He took to the genre like a fish to water, filling film after film with dancing imps, grinning moons and constellations represented by beautiful women. He countered the limitations of silent film by ramping up the fantasy with frequent special effects and gleefully exaggerated acting (even for the era). While he made many “trick” films, dramas and even documentaries, his fairytales are probably what many of us associate with the Méliès name today.

The Infernal Cauldron (1903)

His féerie masterpiece is certainly The Kingdom of the Fairies (1903), a gorgeous work of art with all the detail of a Baroque church. I dare you to watch its charm overload of trompe l’oeil sets, cardboard whales and chariots pulled by painted cardboard fish without practically shedding a tear of joy.

The féerie’s influence on 19th and early 20th century pop culture can help us understand many whimsical works of literature and art, not just the cinema. Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker is a féerie-ballet. The writings of Lewis Carroll, J.M. Barrie and L. Frank Baum were very much in the vein of the féerie. Jules Verne even tried his hand at writing one in his 1881 novel Journey Through the Impossible. Winsor McCay’s stunning Little Nemo comics are much indebted to the genre’s imaginative possibilities. When Baum’s The Wizard of Oz was turned into a musical spectacle in 1902, the director’s choice to include songs and elaborate dance numbers was obvious in the tradition of féerie plays. (And might I add that Larry Semon’s often-derided The Wizard of Oz suddenly seems a lot less strange when you know the context he was working with!)

A photo from The Wizard of Oz‘s 1903 Broadway run.

I’d say it’s no accident that folks continue to be drawn to Georges Méliès’s fairytale work all these decades later. It may be very “of its time,” but that’s the beauty of it. It can serve as an unabashedly naive escape no matter what the troubles or foibles of each new generation. Today, it’s a particularly refreshing antidote to today’s trend of “gritty realism” and the general lack of surrealism in most mainstream films, not to speak of our diminished capacity to appreciate romanticism (as I often feel).

Méliès’s granddaughter would later say of him: “It is not surprising that today we discover the freshness and the enchantment of his work, for he remained very close to his dreams and the poetry of his childhood.” And thankfully for us, the poetry he saw in those childhood féerie plays has been forever preserved in his indispensable work.

—

Sources:

Fell, John L., ed. Film Before Griffith. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983.

Moen, Kristian. Film and Fairy Tales: The Birth of Modern Fantasy. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2013.

Zipes, Jack. The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Reblogged this on Travalanche and commented:

The wonderful, thorough, and scholarly blogger Lea Stans is blogging about Georges Méliès all month. I caught her third installment yesterday. Go here to check it out, as well as the earlier and upcoming ones! A subject well worth celebrating!

So happy you enjoyed it, Trav!! 🙂

Very nicely done. I’ll probably refer to this in my upcoming discussion of Alice Guy-Blaché, who also worked in the Fariée genre early on.

Why thank you! Looking forward to the Alice discussion. 🙂

You might usefully add to your reading lists Georges Moynet, Trucs et Décors, la Machinerie Théatrale (Paris1893). Matthew Solomon’s Disappearing Tricks, the essays of Frank Kessler (the foremost authority on the féerie), and Mariann Lewinsky’s notes accompanying her DVD of Albert Capellani’s Le Pied de Mouton (1907).

I appreciate the recommendations, thanks David!

Most interesting article! I was completely unaware of the féerie genre. It’s an eye-opener to see that Méliès was working out of that tradition—and also how it continued to influence after Méliès. And I love the stills you chose to illustrate the text. They bring to mind one of the things that fascinates me about Méliès—that strange juxtaposition of the technical effects and the Victorian imagery.

“Today, it’s a particularly refreshing antidote to today’s trend of “gritty realism” and the general lack of surrealism in most mainstream films, not to speak of our diminished capacity to appreciate romanticism (as I often feel)”

— you got that right, and the “realism” keeps getting grittier, it seems. 🙂 We could all do with a bit more whimsy and enchantment, féerie-style.

Which reminds me…part of the reason so many people–and critics–loved La La Land was because of its little surreal moments and romantic story. Those things alone made it stand out, which in my opinion shows there’s a hunger for them in our modern culture.

Reblogged this on hoarding hollywood and commented:

Lea at Silent-ology not only reports interesting information on Méliès’ film style, she also gives an excellent contextual background of the theatrical trend of the times that influenced his film-making style. Kudos to you, Lea!

My pleasure! 🙂

Pingback: Alice Guy-Blaché: Mother of Film | Century Film Project

Pingback: Obscure Films: “The Blue Bird” (1918) | Silent-ology

Pingback: Silent-ology Turns Four Today! | Silent-ology

Pingback: Thoughts On: “Peter Pan” (1924) | Silent-ology

Pingback: Albert Capellani: Two Feeries | THE WORLD FILM HERITAGE 1895-1915

Pingback: Thoughts On: “The Devil In A Convent” (“Le Diable Au Couvent,” 1899) | Silent-ology

Pingback: ‘Viaje a la luna’ de Méliès, el espectáculo eterno – Así habló Zamuthustra