One of the few silent classics virtually anyone’s willing to watch, Nosferatu has been iconic practically since its release in 1922. The strange, hunched Count Orlok has a permanent place in cinema history, a unique pedestal that keeps him apart from the suave villains of later pop culture.

I’ve reviewed this gothic masterpiece before, but didn’t delve much into the details of how or why it was made. A few of you may already know the tale, with its background of modern art, WWI, occultism, flu epidemics, and gleeful copyright infringement. But if not, do read on.

This film version of Bram Stoker’s popular novel Dracula was indebted to Albin Grau, an architect, artist, and significantly, an occultist (sounds about right). He’d been deeply affected by his service in the German army during World War I, a war that he later called a “cosmic vampire.” In fact, while promoting Nosferatu, the theatrical Grau submitted an article to film journal Bühne und Film recounting how he supposedly met a Serbian farmer who claimed his father had been a vampire, vanquished by a stake through the heart. This was meant to illustrate the war’s connection with a fearful, almost supernatural bloodlust. At any rate, it made for a good publicity story.

At some point in 1921 Grau met F.W. Murnau. A cultured and somewhat frosty individual with a perfectionist streak, Murnau had worked for German theater giant Max Reinhardt and was known for his deftly-directed Expressionist films. He also had served in World War I, where he’d been part of Germany’s Flying Corps and had survived no less than eight plane crashes with only minor injuries. Murnau told Grau that he wanted to turn Stoker’s Dracula into a feature; intrigued, Grau decided to turn film producer and work with this talented director.

Striking up a partnership with businessman Enrico Dieckmann, Grau started a small film studio that he dubbed Prana-Film, “prana” being a Hindu term for “force of life.” Weimar Germany was rife with these little studios, and Grau had designed posters and other promotional materials for a number of them. The duo had grand plans for three initial films: Hollenträume (Dreams of Hell), Der Sumpfteufel (The Devil of the Swamp), and finally, Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu, A Symphony of Horror)–not for nothing was Grau the member of secret occult societies.

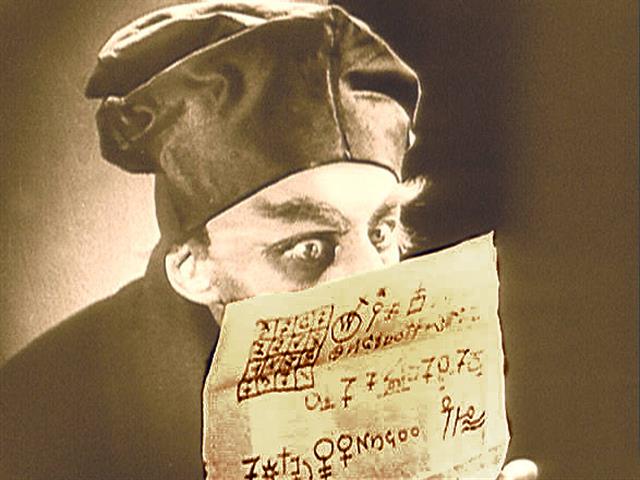

These were real occult symbols, by the way.

But how to film Dracula, when Prana-Film didn’t technically have the rights to it? Waving such petty details aside, Grau and Dieckmann decided to change a few character names and call it a day. For this job they hired Henrik Galleen, a screenwriter who had worked on The Golem (1920). Not much is known about his early life, but he plenty of film industry experience and had also worked for Max Reinhardt. He changed Jonathan Harker’s name to Hutter, Mina to Ellen, Renfield to Knock, Count Dracula to Count Orlok, and so forth. Most significantly, he referred to Count Orlok as “Nosferatu.”

It seems fitting that even the term “Nosferatu” has a mysterious origin. Galleen’s source was one of Bram Stoker’s research notes, which referred to an 1885 article by travel writer Emily Gerard. Gerard had talked about the “nosferatu,” or vampire, that supposedly came from Romanian folklore. Besides Gerard, there are one or two other 19th century writers who also referenced the nosferatu. One problem: nosferatu is not a word that appears in the Romanian language. Possibly, someone at some point had mistranslated nesuferitu, Romanian for “unclean” or “the Devil.”

Other changes included switching the main locations from England to Germany, which was Murnau’s idea, as well as making sunlight fatal to Nosferatu rather than just weakening him. He and Galleen also saw Nosferatu as symbolic of not only the war, but the Spanish flu epidemic that had hit Europe from 1918 to 1920–killing millions of people. The pale vampire with his horde of plague-carrying rats would have far deeper significance than a few onscreen chills.

Thus far, we have a businessman, an occultist with a flair for drama, an Expressionist director with a perfectionist streak, a screenwriter with an obscure past, a mystically-named mini studio, and a strange film title using a word that doesn’t technically exist. What next, but to hire a suitably eccentric actor to portray Nosferatu?

German theater actor Max Schreck fit the bill–almost too well. His last name is German for “fright,” for pete’s sake. Little is known about him, mainly that he was born in Berlin, his father was a civil servant and he was married to a theater actress (they didn’t have children). A loner with an odd sense of humor, he was described as enjoying long walks through dark forests. Although he appeared in over 800 theater roles–he was adept at “grotesque” characters–precious few anecdotes exist about him.

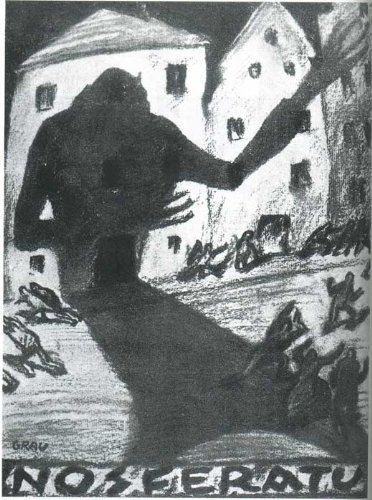

Grau masterminded the character and set design and also designed the posters and promotional materials. Some of these promos shamelessly declared: “Freely adapted from Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” (Prana-Film might’ve thought the new character names were enough to ward off copyright infringement–and they’d probably gotten some spectacularly bad legal advice.) The posters are pretty eerie even today, and show the influence of Romanticist and Surrealist artists like Alfred Kubin. The film was made in the summer of 1921 and relied heavily on location shooting, mainly because of Prana-Film’s small budget. And here’s a piece of trivia–they put out a casting call for rats.

Reckless in pretty much every way possible, Prana-Film then spent a fortune on Nosferatu‘s promotional campaign and hosted a grand premiere on March 4, 1922 at the Marmorsaal (“marble hall”) of the Berlin Zoological Garden (guests were encouraged to wear early 19th century clothing). This all gave Nosferatu incredible publicity, but almost bankrupted the studio.

And it officially went bankrupt once Bram Stoker’s widow Florence pounced on Prana-Film’s copyright infringement. Tipped off by an anonymous letter, she took the studio to court and after a few years of struggle won her case in 1925. And thus the ambitious little German studio folded, having only released a single film–Nosferatu. Which, by the way, Florence almost wiped from the face of the earth. She tried to have every reel rounded up and destroyed, but enough copies had been floated around that the venture proved impossible.

Following the strange saga of Nosferatu, Murnau would go on to create masterpieces like Faust (1926) and Sunrise (1927), Galleen would make The Student of Prague (1926) and Alraune (1927), Grau would leave his occult societies after the bickerfest that was the 1925 Weida Conference, Max Schreck returned to the busy obscurity where he seemed the happiest, and Nosferatu became regarded as one of the greatest horror films of all time.

And that, my friends, is the rest of the story!

—

Sources:

Giesen, Rolf. The Nosferatu Story: The Seminal Horror Film, Its Predecessors and Its Enduring Legacy. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019.

Massaccesi, Cristina. Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. Great Britain: Auteur, 2015.

Skal, David J. Hollywood Gothic. New York: Faber and Faber, Inc., 2004.

Blakeney, K. (2011). “F.W. Murnau, His Films, and Their Influence on German Expressionism.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 3(01).

Thank you for this excellent round up on Ol Nos as we called him in grad school. Love this movie, never knew the fascinating background. Still creepy ( Lotta those rats still around now…)

Many movies’ backstories are pretty prosaic–the producer picks a project, a group of seasoned professionals get to work, the actors do their thing, nothing too out of the ordinary.

Then there’s NOSFERATU. 😀

Pingback: “The Ultimate Trip”: Stanley Kubrick, Stanford’s Saturn Cult, and Star Wars Counterculture (Part One) – Beyond_Lies_The_Wub

Pingback: A Century Of “Nosferatu” (1922) | Silent-ology

Pingback: Greta Schröder, The Quiet Heart Of “Nosferatu” | Silent-ology

Pingback: How Did “Nosferatu” Make It To The U.S.? | Silent-ology