Post #1 of Soviet Silents Month is here! I hope you enjoy reading about this fascinating (and rather intense) area of film history!

Few things summarize our idea of Soviet silent films better than the opening of the 1968 restoration of Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Mother (1926). As a projector (audibly) sputters to life, through a swirl of artificial snow a bold white “1905” looms on the screen. Snow continues to swirl around a series of black and white illustrations of the 1905 Russian Revolution, showing masses of the working class squaring off against soldiers in wintery city squares. The music is bombastic–deeply dramatic. The screen fades to black. And then it’s filled with a rather wordy quote by–who else?–Vladimir Lenin.

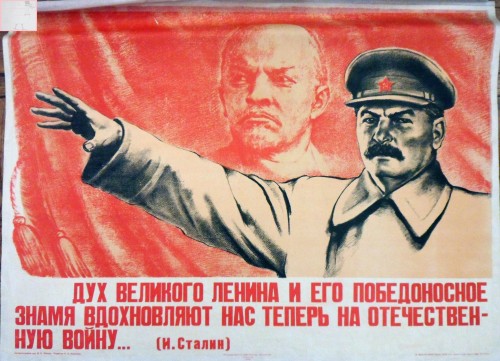

A dramatic poster for Mother (1926).

You’re no doubt assuming I’m going to say that there’s more to Soviet silent films than government-approved propaganda–including 1968 imitations of government-approved propaganda. There were delicate dramas and rollicking comedies made in Russia just like everywhere else, it’s true. However, they were always released with a catch. For from the early 1920s onward every film in the USSR was squeezed through the sieve of government censorship, including American imports (which were wildly popular). Analysis of Soviet film must forever dance between admiration of the finest examples of its artistry, and recognition that much of that artistry was in service of communist propaganda–often willingly.

From October (1927)

And thus the history of Russia’s bold, futuristic, cutting-edge early cinema is a fascinating one, and well worth consideration. Few other nations would seize on a new form of expression as doggedly as the Soviet government. And few filmmakers would reach such heights of artistic achievement within such increasingly rigid confines, causing such a global superstar as Douglas Fairbanks to declare in 1926: “The finest pictures I have seen in my life were made in Russia. They are far in advance of the rest of the world.”

Footage of Tverskaya Street in Moscow taken in 1896.

Cinema debuted in Russia around 1896, thanks to those familiar public demonstrations of Lumière and Edison films. In fact, one of the most famous passages about early cinema was penned by writer Maxim Gorky, who saw a Lumière demonstration at the Nizhnii Novgorod fair. His “cold-reading” of the strange new technology, as familiar as water to us today, is astonishingly fresh–even startling:

Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows.

If you only knew how strange it is to be there. It is a world without sound, without color. Everything there–the earth, the trees, the people the water and the air–is dipped in monotonous grey. Grey rays of the sun across the grey sky, grey eyes in grey faces, and the leaves of the trees are ashen grey. It is is not life but its shadow, it is not motion but its soundless specter…

Suddenly something clicks, everything vanishes and a train appears on the screen. It speeds straight at you–watch out! It seems as though it will plunge into darkness in which you sit, turning you into a ripped sack full of lacerated flesh and splintered bones, and crushing into dust and into broken fragments this hall and this building, so full of women, wine, music and vice.

But this, too, is but a train of shadows.

Of course, not everyone who took in the wonder of the motion picture brooded over thoughts of hall-crushing and instant death. Critic Vladimir Stasov saw an Edison demonstration that same year, and enthused in a letter to his brother:

What joy I had on Monday, seeing the moving photographs, that magnificent new invention of the genius Edison…It is really extraordinary, resembling nothing previously known, and indeed it could not have existed before our century…

The thing isn’t perfect yet, of course, for the figures and objects and the background often blink and shake…but how can the idlers speak against this magnificent achievement! When a whole train flies from the distance, tearing aslant through the picture, what comes to mind in that very second is the same image in Anna Karenina–it’s almost unimaginable.

The first film made in Russia was footage of the crowning of Tsar Nicholas II, taken in May of 1896 by a Lumière crew. But the second film would never see the light of day (so to speak). Two days after the coronation, the new Tsar was presented to the public in a huge outdoor ceremony attended by thousands of Russians. The Lumière crew was on the scene when tragically, rumors that refreshments and commemorative gifts were running out triggered a massive crowd crush. 1400 people were killed in the chaos. The shocked filmmakers documented several reels of the disaster, but their film and cameras were quickly confiscated and never seen again.

Screengrab from Tsar Nicholas’s coronation film.

And thus, the first ever hand-cranked cameras in Russia documented both the last Tsar during the final years of the mighty Russian empire, and great tragedy involving the Russian people that was quickly covered up. You could see these events as strange microcosms of that country’s operatic history, and perhaps omens of the future.

Cinema in the Time of Revolution

While motion pictures were more of a novelty for city folks at first, during the 1900s entrepreneurs began touring villages, setting up screens and benches out in the open air and showing their short films once the sun went down. One enterprising soul had a barge travel down the Volga river with a projector, a kind of early cinematic showboat for the intrigued peasants. In 1908 Pathé filmed The Cossacks of the Don in Russia, which was a major hit. It wasn’t long before Russian-run studios started springing up, mainly in Moscow, busily producing dramas, comedies, and costume pictures. A tendency toward tragedy was common in these films–sometimes two endings were filmed: a sad one for the Russian public and a happy one for exporting to the west.

Father Sergius (1918).

As cinema was evolving, two huge events rocked the country. The first was the 1905 Russian Revolution, the result of growing resentment by the working class toward the political system and an economy that was in rags. Resentment continued to simmer for the next few years, especially as people began flocking to the crowded cities for work. The outbreak of WWI dealt another blow to Russia–it would suffer catastrophic losses.

Finally, all the tension came to a head in 1917 as massive strikes, demonstrations and violent riots toppled the Tsar’s rule. Seizing control were the radical Bolsheviks (later called “Soviets”), lead by Vladimir Lenin. Positive they could build a new post-Tsarist society from the ground up, they began implementing socialism, with the end goal being a Brave New World of communism–at any cost.

Pro-communist propaganda was to be a massive part of this society-building. It’s hard for us today to understand just how pervasive and organized it was. Directives published in the Soviet-controlled Pravda newspaper stated: “The cinema theater, concerts, exhibitions, etc., as much as they will penetrate to the country, and towards this end all forces must be applied, must be used for communist propaganda directly…There is no form of science or art which cannot be linked with the great ideas of communism and the infinitely diverse work of building a communist economy.”

Film would be key to this propaganda-spreading. By the mid-1910s, cinema was massively popular–there were over 1400 cinemas in Russia (most being in cities). When we consider that only 2 out of 5 Russian adults were literate at the time, it’s not surprising that Lenin would call film “the most important of all arts.” The Soviets quickly created a new state-controlled company, Narkompros, to properly control this promising industry.

Early experiments with propaganda created a new genre: agitki, or short newsreels (at times so short they resembled living posters) with approved party messages. One example is Proletarians of the World Unite (1919). Scenes of the French Revolution are followed by an earnest title card declaring: “The French Revolution was defeated, because it had no leader and it had no concrete program around which the workers could have united.” Viewers then saw Karl Marx (well, an actor) writing “Proletarians of the world unite!” Special agit-trains and agit-steamers regularly carried these not-so-subtle mini-films to the public.

Part of a highly decorated agit-train.

State control of the film industry was tepid at first, what with the poor economy, civil unrest, effects of WWI and the Russian Civil War that followed the 1917 revolution and all. Agitki made up the vast majority of Soviet-made films. But this would soon change.

Just A Little Capitalism

Not too surprisingly, after all the devastation of the 1910s the Soviets’ total societal overhaul wasn’t going too well (famine even broke out in 1921). Lenin created the temporary New Economic Policy (NEP), which grudgingly allowed for some capitalism. This quickly kickstarted the economy, and in turn the film industry. In 1921, filmmaking in Russia had practically ground to a halt. By the end of the 1920s, the cinema of the USSR would be one of the most admired in the world.

Soviet filmmakers swiftly discovered fresh, sophisticated ways to make compelling cinema (often with little resources). D.W. Griffith’s scene-shuffling Intolerance (1916) was very influential (rumor has it Lenin wanted Griffith to come oversee the Soviet film industry), as was the avant-garde. The All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) would be the world’s first film school, and boasted teachers like Lev Kuleshov who taught the power of editing. His famous “Kuleshov effect” showed how the same shot of a man’s face appeared to subtly change expression when followed by different images–a remarkable editing illusion.

Many Soviet directors treated filmmaking much like engineering, pieces together shots in different ways and frequently bouncing different theories off of each other. One of Kuleshov’s students was the Sergei Eisenstein, who would film the propaganda masterpiece Battleship Potemkin (1925). Fascinated by montage, the intellectual Eisenstein developed theories on its uses and honed it to a fine, emotional science. He would be commissioned by the government to turn out other artistic propaganda like October (1927) and Old and New (1929), which glorified the Russian revolution and collectivization.

Battleship Potemkin.

All of these innovations and more would unfold under Soviet supervision, of course. In 1922, Lenin wrote:

It is necessary to show not only films, but also photographs which are interesting from the point of view of propaganda, with appropriate subtitles. Movie houses which are in private hands should give sufficient income to the government in forms of rent. We must give the right to entrepreneurs to increase the number of films and to bring in new films, but always under the condition of maintaining the proper proportion of films of amusement and films of propaganda character, under the heading “from the lives of all people”…

Films of propaganda character should be given for evaluation to old Marxist and literary people in order to make sure that such unfortunate events in which propaganda has backfired are not repeated.

Special attention should be given to the organization of movies in villages and in the East where this matter is a novelty, and therefore our propaganda should be especially successful.

Under increasing censorship, filmmakers had to do their part to uphold the party line–sometimes shoehorning it in. In The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West In the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) the American Mr. West witnesses a pro-Bolshevik rally and promptly writes his wife to “put up a picture of Lenin.” The hero of science fiction feature Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924), which featured eye-popping Constructivist sets and costumes, preaches about the 1917 revolution to Mars citizens and declares: “Follow our example, comrades. Form one working family of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics of Mars.” Foreign films were carefully scrutinized by the state-controlled Sovkino according to communist ideology. Mary Pickford, who so often portrayed working-class waifs, was given a thumbs-up. But someone like Gloria Swanson, who floated through DeMille “society pictures” in expensive gowns, was practically unknown to the Soviet public.

Not-So-Rebellious Modern Artists

The popular view of modern art is that it was rebellious, a thumbing of the nose at “convention” and overly-prim society. This wasn’t the case in the 1920s USSR. We have to remember that the Bolsheviks were convinced that turning their backs on the “old ways” would ring in a utopian, machine-filled future. And what could be more modern, and more futuristic, than futuristic modern art?

Six Girls Seeking Shelter (1927)

In the early 20th century modern art movements were on the rise, and one of the biggest was Russia’s own Constructivism. Started by Vladimir Tatlin in 1913, it gained steam during the 1910s but became all the rage in the 1920s–with the state’s blessing. Armed with slogans like “Art into Life,” the Soviets considered Constructivism an ideal style for the grand goal of “bringing art to the masses.” With its bold designs that played with unusual perspectives and industrial motifs, Constructivism cropped up in art, theater, fashion, architecture, and most notably, stunning poster design.

Yego Kariera (1928)

Buoyed by this trendy interest in all things futuristic and happy to create art in service of the anti-bourgeois cause, Soviet filmmakers like Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, and Vsevolod Pudovkin experimented with dramatic angles, quick editing, and of course, montage. They had a bit more creative freedom during Russia’s version of the “Roaring Twenties” than they would under Stalin, and the result was a multitude of powerful classics like Battleship Potemkin, October, The End of St. Petersburg (1927) and The Man with a Movie Camera (1929). And the authorities approved: “Who will deny that these men understood the line of the Communist Party and expressed it excellently in their work?”

Interestingly, it may have been Douglas Fairbanks who helped introduce Soviet films to the west. After a visit to Moscow with Mary Pickford in the mid-Twenties, he told the press: “I used to think I knew something about conveying emotion through movement. But when I saw Eisenstein’s work, I realized I hadn’t begun to learn.” Critics around the world began to admire the sophistication of Soviet cinema–although in the USSR itself, most regular folks preferred American comedies and adventure stories, which were often bootlegged.

The End of a Quasi-Golden Age

As the 1920s drew to a close, censorship of films was becoming increasingly strict as the state obsessed over the “correct” communist ideology. Even greats like Eisenstein were beginning to be regarded with suspicion, perhaps because of fear that “artistic” fare would go over the lower classes’ heads. Being too artsy simply wasn’t a reliable way to hammer in the party line–especially when dealing with peasants, who had the exasperating habit of clinging to the “old ways.”

Director Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s pro-collectivization feature Earth (1930), with its meditative shots of nature and rural life, was condemned as “counterrevolutionary” and even a “kulak film” (for Communists, a massive insult). The great Kuleshov himself was angrily denounced for his “vulgar desire to give to the audiences what the audiences wanted” (the nerve). And Vertov, once the fieriest of revolutionaries, was criticized for being more interested in being experimental than being radical (he’d released an ambitious sound film).

Once Stalin took control, “Socialist Realism” became the state-sponsored style, and what some historians would refer to as the Soviet Union’s “Golden Age of Cinema” came to an end. As the years passed, fewer and fewer films would be made as Stalin’s brutal regime grew obsessed with what can only be described as ideological purity.

This has been a necessarily barebones look at the history of Soviet cinema, a topic that would take a lifetime to properly explore. As the fog of propaganda recedes further and further into the past, we can more properly see Russia’s lasting contributions to cinema–the art of editing and montage that we still see in every movie trailer today–those confident techniques that have proved to be timeless.

—

Sources:

Kenez, Peter. Cinema and Soviet Society: From the Revolution to the Death of Stalin. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2001.

Leyda, Jay. Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1983.

Goessel, Tracey. The First King of Hollywood: The Life of Douglas Fairbanks. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2016.

Pack, Susan. “Film Posters of the Russian Avant-garde.” 1995. http://tomlundquist.us/Packtxt.htm

http://www.silentfilm.org/archive/a-kiss-from-mary-pickford-1927

Absolutely fascinating and impeccably researched. This couldn’t have been an easy one to write!

I have to laugh because the same thing happened with rock and roll records in the 60s and 70s. I’ve heard it said that rock & roll records and desire for blue jeans had as much to do with bringing down the Soviet Union as anything else, lol. Reading this article, obviously it was the fun of Western culture that did it, the seeds going back to those old American silents. 🙂

PS: I think I spelled your name “Leah” in my last comment, so sorry. I have a friend who spells it Leah, I get mixed up sometimes when I’m typing too fast! I endeavor not to make that mistake again!

It was, shall we say, A CHALLENGE to write. 😀 There was so, so much material to wade through, and so much stuff that could’ve been included. What was the most essential info? Was it getting too long? (I’m allergic to making articles too long.)

“The seeds going back to those old American silents”–I love that! I’ll bet you’re right!

You typed it, By The Clock, “ABSOLUTELY FASCINATING”!!!! Thanks so much!! I really do enjoy your work, Lea!!! 🙂

You’re so welcome!! Comments like this make all that work worth it. 🙂

Being a Russian myself, I have an additional sentiment to these movies. They are part of our culture, even though Communism is not here already, bits and pieces are still left in us. Thank you so much for this post.

One thing, this pic in your post is a joke. The text in Russian says “Please go and F yourself, comrade”.

https://radikal.ru/lfp/s53.radikal.ru/i140/1010/c7/82b432ca2b7d.jpg/htm

You can replace it with this one: https://www.meme-arsenal.com/memes/60555cf6f56b9a20f3fe834788f56a0c.jpg

Or Google Ленин вперёд, товарищи to find other pics

I look forward to reading more of your posts!

You’re welcome, Vasily–I appreciate your visit! And thanks for pointing out the “joke” picture. I’ll admit, I ran across quite a few memes while looking for ‘legit” Soviet posters and one snuck in there. 😀 (Although, this meme kind of fits…naw, I’ll replace it.)

Awesome post, Lea! You managed to make it entertaining and informative, and it was a darned good survey of Soviet cinema. Thank you for doing all the hard work of parsing this and that from your source material and sharing it with all of us. Kudos to you!

Aww thanks–I really appreciate it!! It took a lot of thought and revision to boil everything down to the most essential info (I hope), and also not make it too dry. There’s always more that could’ve been discussed, of course, but gotta keep it a reasonable length…!

That was very interesting! I love the Six Girls Seeking Shelter poster!

Glad you enjoyed it, Virginie! That’s one of my favorite Soviet posters, so striking. 🙂

Pingback: It’s Silent-ology’s Seventh Anniversary! | Silent-ology

Pingback: 10 Best Soviet Silent Comedy Films - High On Films