Post #1 of Sheik Month is here! Hope you enjoy!

We’re all familiar with stereotypical 1920s flapper–the fun-loving, trendy young woman who loved Jazz, dancing, and all things “modern.” But arm in arm with the flapper was the 1920s sheik, their male counterpart. There’s plenty of discussion about flappers nowadays, but there’s comparatively little discussion about sheiks, and the sort of factors that lead to their place in pop culture.

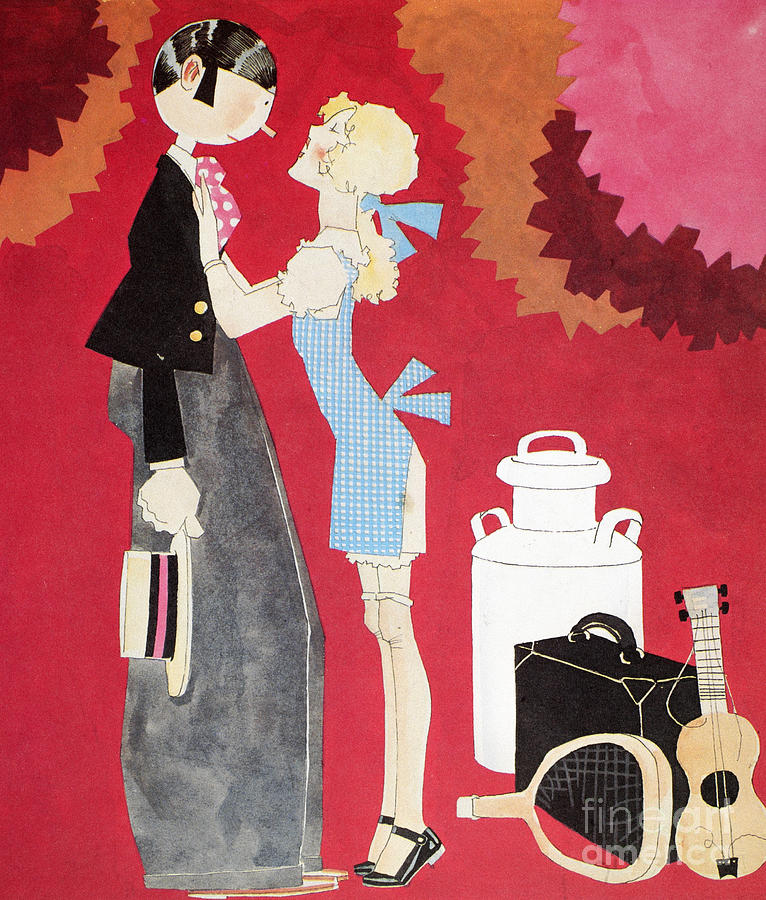

One of John Held Jr’s popular cartoons.

But “sheik culture” is an important piece of the Jazz Age puzzle. Its advent spurred numerous discussions about movie romance, masculinity and female desire. And its impact on American cinema was tremendous–in fact, you could easily categorize screen romance as B.V. (Before Valentino) and A.V. (After Valentino).

Some Background

As communication, transportation, and everyday life began speeding up in the early 20th century, young people were keenly aware that times were changing. The industrial revolution was in full swing, and thousands flocked to the cities to work in factories. This included numbers of child laborers, who often endured unsafe working conditions. On the flip side, newfangled “modern conveniences” promised to eventually ease labor in the average home and contribute to a prosperous new era. The rise of the automobile was an exciting development too–we can imagine it was extra exciting to children, and especially to young boys.

There was also a general sense of optimism about the new century. It seemed to be expected that life would improve, and that bright futures were in store for anyone with the gumption to work hard. There was also a sense of adventure in the air. The latest president, war hero (and former cowboy) Theodore Roosevelt, was a major role model. Stories swirled through the newspapers about gold rushes in the West, polar explorations in the North, safaris in Africa and the wondrous new “aeroplane.”

Most young people would’ve been familiar with the adventure stories of Jules Verne and H. Rider Haggard, as well as the ubiquitous dime novels. These affordable pamphlets had been wildly popular for decades, with boys in particular being attracted to countless sensational stories about the Wild West, historic battles, pirates, crime-solving, and more. Many of the heroes of these stories were boys who managed heroic feats or lucked into fabulous inheritances, the type of escapism that had broad appeal to young imaginations.

From the venerable Lileks.com

By the 1910s, the young men who grew up with adventure stories and the exciting new era of cars and mechanical marvels would’ve been aware of many topics of the day. Major ones were the role of masculinity and the idea of the “new woman,” since the suffragette movement was on the rise. One prominent “freethinker,” Rosa Mayreder, wrote in the New York Sun:

The true origin of the change that is taking place in the position of the female sex will never be understood rightly so long as the change in the condition of life in the male sex remains unconsidered. The two sexes are so closely related, are so dependent on one another, that the conditions which affect the one must affect the other.

Opinions on the sexes were being shared around the same time jazz was becoming popular–many young men met their “sweethearts” at the crowded dance halls–and where the jazzy cities had unique blends (and clashes) of cultures in a rapidly growing economy. And, of course, all these topics were touched upon in Hollywood films, which would soon have a massive impact on these national conversations.

In the midst of all this change came the biggest–and most painful–one of all. World War I was a global turning point, and millions of young Edwardian men witnessed it firsthand. The mud of the trenches and nerve-shattering shellfire were a far cry from the romanticized battles of the old dime novels. When the war ended in 1918, a generation of former soldiers found themselves adrift, surrounded by a world-weary public who had no idea what they endured. The joie de vivre of the 1920s was a way to move on from the war–or perhaps a way to reconcile with the fleeting nature of life.

Enter Valentino

Prior to 1921, leading men in films tended to be staid, dependable sorts with the auras of well-heeled businessmen. Generally, there were boyish types like Robert Harron or Jack Pickford, or clean-cut types like Thomas Meighan or Harold Lockwood. Handsome Wallace Reid and muscular Francis X. Bushman had their followings as well. The popular Sessue Hayakawa was one of the closest to the sheik of 1920s romances, since his Japanese heritage made him “exotic” to Edwardian women and his “forbidden lover” roles gave him an edgy appeal.

But these trends would change once a certain Rudolfo Guglielmi was on the scene. An ambitious young Italian immigrant who adopted the screen name “Rudolph Valentino,” he had popped up in various films in the late 1910s. His dark (-ish) complexion and good looks usually typecast him as a suave villain, but in 1921 he would be given his breakout role: as Julio in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Valentino’s Julio was confident, handsome, and undeniably virile. His tango dance early in the film made legions of women instant “Rudy” fans.

Valentino further cemented his appeal with his lead role in The Sheik (1921), based on E.M. Hull’s lurid novel about a desert sheik who kidnaps an impetuous young Englishwoman. Despite a predictably silly plot, Valentino was again a sensation.

The film prompted much discussion on the pros and cons of “caveman” wooing–women were undeniably attracted to the fantasy of a powerful exotic lover consumed with desire for them, at least from the safety of the movie theater seats. (One gal wrote to a fan magazine: “I don’t like the nicey nice man who says ‘please, dear’…I like a real man who won’t be ordered around.”) The Sheik kicked off a craze for “desert romances,” imitated by films such as One Arabian Night (1921) and A Son of the Desert (1923). Actors from Milton Sills to Ramon Novarro to Ricardo Cortez lined up to be called “the next Sheik.” The label “sheik” itself became a household word.

The particular appeal of Valentino came at just the right time. Throughout the 1910s there had been a growing fascination with the exotic, especially “Orientalism.” The Far East was considered a place of mystery, sensuality, and lush beauty. The desert, especially, was thought to be a place where passions still ran wild, unrestrained by your average polite society. Trend-setters flocked to Eastern-inspired clothing, lacquered tables, incense, and even turbans. The Sheik’s desert romance was very much part of an overall trend. Even Valentino’s Italian heritage–which made him a tad exotic in that time period–fit into it nicely.

Many young men, more interested in the exploits of Douglas Fairbanks or Tom Mix, rolled their eyes at women’s fawning over that “foreign” Valentino. But some were fans, or least tried to emulate his style to signal that they were a more dashing breed than their (supposedly) genteel elders. His usual hairstyle–slicked back and glossy with hair grease–became of the most recognizable male trends of the 1920s. A joke “Motion Picture Dictionary” article from Photoplay defined an “antimacassar” as: “a doily placed on the back of chairs to protect the upholstery from the oiled and pomaded heads of motion picture actors.”

Oiled and pomaded. (Image source: Vintage Dancer)

With the interest in dashing Latin Lovers like Valentino at such a height, young men–particularly those dandified types who loved jazz, girls and fast cars–were being jokingly referred to as “sheiks.” The label stuck–indeed, some seemed to wear it with pride. It would be common to hear about the partying ways of the bell-trousered “sheiks” and their bobbed-haired “shebas” until the end of the decade.

The “Plastic Age” In Full Swing

The sheik trend coincided with the interest in the growing college campus culture. After World War I, young men and women were attending college in record numbers. Kids didn’t just want to study–they wanted the thriving social life the campus promised. Much like flappers, sheiks were eager to prove their modernity and fit in by adhering to the latest styles. A collegiate youth rarely left the house without a sporty hat, patterned sweaters, and of course, Oxford bags. Raccoon coats were also massively popular and became a kind of status symbol–as well as handy for those chilly football games. (And don’t forget that hip flask.)

Soon these “modern” young men were making appearances in songs, comic strips and numerous films. Hollywood would lampoon sheiks nearly as often as flappers, especially in “college films” (where nary a textbook was ever in sight) and in comedies like Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman (1925). Young Eddie Quillan, who worked for Sennett for a few years, played a series of boyfriends, soda jerks, and other teen characters, usually sporting Oxford bags and a straw hat with a bold hatband.

Buster Keaton also spoofed campus styles in Steamboat Bill Jr, where his dandified character sported every sheik-loving cliche from loud sweater vests to striped blazers:

Image courtesy of my friend Trish.

Folks, of course, continued to raise their eyebrows at the supposed excesses of the modern youth culture, whether real or exaggerated. Some took a pragmatic approach–an article in a 1923 Vancouver Sun quoted a Dr. LaForge, who said, “Sheiks and shebas are victims of the same disease, a disease typical of the age. And there is only one cure for it–work!…Give them an outlet for their activity, an emergency to meet, and there’ll be no more sheiks and shebas.” Dr. LaForge then reassured readers that “the outward manifestations, the bell trousers, the flat derby…were fantastic, but quite harmless.”

Exit the “Sheik”

Valentino would pass away suddenly in 1926, due to an infection caused by a gastric ulcer. And by the end of the Roaring Twenties, both the sheik and his flapper was going out of style. The optimism, partying, and innocent flirtations of “college films” would start to seem dated next to the sarcastic dames and hard boiled gangsters of the ’30s and beyond, and that mirror-shiny hair gloss and baggy trousers started to look very “of its time.”

But it was a unique period where men were perhaps more keenly aware of feminine tastes and desires than in the previous decades. This awareness certainly had its effects on innumerable young couples. And if the popular romance novels of today are any indication, the essence of the “he-man” sheik–the man who “can’t be ordered around”–still has its secret appeal.

—

Sources:

Koszarski, Richard. The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915-1928. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990.

Leider, Emily W. Dark Lover: The Life and Death of Rudolph Valentino. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003.

Walker, Brent E. Mack Sennett’s Fun Factory. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010.

“Sheiks, Shebas Harmless, Sure Cure is Hard Work.” The Vancouver Sun, Vancouver, British Columbia, July 12, 1923, page 12.

Enjoyable read and oooo… those Oxford bags!😂😂

Fashion as an aid to be “cool” strikes every generation!

😀 Imagine what they’d think of today’s skinny jeans (and skintight leggings) craze.

I love the titles you’re coming up with lately. This one and “Buster’s Wife’s Relations” are particularly brilliant. 😁

Interesting article! I’ve seen the word sheik used here and there but never gave it a whole lot of thought- it’s nice to get the full scoop.

And I love that Valentine (not a typo for Valentino, honest!). Where’d you run across it?

It happened to pop up online when I was searching for “sheiks and shebas” images. Isn’t it perfect?!

Must say, it was surprisingly hard to find regular, everyday photos of young 1920s men (rather than pictures of actors). Flapper photos are all over the place, but there’s not so much that’s sheik-related. There’s probably a lot of fun stuff tucked away in archives that folks haven’t thought to look through! (Thank heavens for John Held Jr, btw.)

There are still a LOT of ladies who–sometimes not consciously known even to themselves–prefer “men who won’t be ordered about.”

No doubt about that! 😉

Loved this post about sheiks. With the 2020’s coming up, I wonder if any of these 1920 trends will be recyled. What is old is new again. 🙂

I say–bring it on!!

Beautifully put together. I hope, myself, to look at his male devotees, who are a very forgotten bunch. As you state Rudy’s timing was immaculate. His portrayal of an Arab in The Sheik (1921) was a like a bomb going off. He soared from Stardom to Superstardom and the rival studios scrambled to imitate it and cash in. The vacuum created by his One Man Strike – 1922 to 1923 – allowed them to field their own Valentinos. This of course only burnished the absent original further; as nobody quite had what he had. Looking forward to Part Two! His fame Still Lives.

It’s on the way!

Rudy certainly had a unique quality that other actors lacked. Sorry, 1920s studios, but Milton Sills? I don’t think so. And Ramon Novarro didn’t exactly exude “danger.” 😉

This is all gold– I love looking back at these youth phenomenons. Makes you realize what we think is awesome today might not keep its appeal in another ten years. Valentino was a fascinating pop icon, especially since he still holds charm for modern silent film fans.

There’s a timelessness about him and his style that’s still appealing, I dare say.

Personally, I think there’s a BOATLOAD of fashion trends today that our kids and grandkids will relentlessly make fun of. It’s like we’re giftwrapping it for them. 😀

Pingback: Well Look At That, Silent-ology Turns 6 Today! | Silent-ology

Pingback: Silents are Golden: The “Sheik” Phenomenon of the 1920s | Classic Movie Hub Blog

I think that should be Hommes Fatales.

By George I think you’re right–thanks!

Macassar is a port city in Indonesia, where fine oil pomades for hair were produced in the 19th century – thus the pomades were called “macassar oil” – because the oily hair pomades left residue on upholstered furniture, doilies placed over the areas where an oiled head would make contact with the upholstery became standard protection of the upholstery fabric and referred to as “antimacassars” – the humor of the quoted remark regarding “film stars” is intended to be an arch observation

Very interesting! I must clarify, however, that this specific reference to “pomaded heads of motion picture actors” was absolutely intended as a joke. Here’s a link to the page from Photoplay. Other “dictionary entries” include “Adonis: An ancient deity of of surpassing facial beauty and perfect bodily proportions, of whom the average leading man secretly regards himself the modern reincarnation.” https://archive.org/details/phojun22chic/page/n463/mode/2up?view=theater